Introduction: The Gavel Strikes Again

There are franchises that thrive on spectacle, and then there are those that survive on something rarer—wit, satire, and the ability to reflect society’s bruises in the mirror of humour. Subhash Kapoor’s Jolly LLB series belongs firmly in the latter camp. Beginning in 2013 with the surprise hit Jolly LLB, the franchise immediately carved itself a space distinct from Bollywood’s usual court-drama template. Instead of sleek sets, heroic lawyers, and neatly tied conclusions, it gave us bumbling, flawed protagonists, systemic rot, and a judge whose eyes saw far more than the law books on his desk.

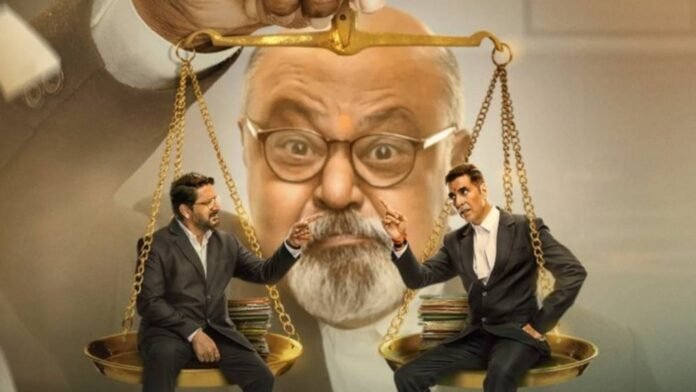

Jolly LLB 2 in 2017, backed by the charisma of Akshay Kumar, widened the film’s reach without abandoning its core DNA. Now, with Jolly LLB 3, expectations were formidable: could Kapoor juggle the irreverence that made the first film beloved, the star power that powered the second, and a socially resonant issue that matters in contemporary India?

The answer, in brief: yes—but with bruises and imperfections, much like the justice system it depicts.

—

The Plot: Two Jollys, One System, and a Widow’s Battle

The story unfolds in Bikaner, Rajasthan, where land is more than soil—it is identity, heritage, and dignity. We meet a farmer clinging to the last parcel of his ancestral land, fighting against predatory acquisitions and financial pressures that seem designed to crush the weak. When the struggle proves overwhelming, he ends his life—another number in the country’s grim statistics of farmer suicides.

Years later, his widow Janki Rajaram Solanki (Seema Biswas in a career-defining role) seeks redress. Lacking money, influence, or allies, she becomes the very image of a powerless citizen fighting a faceless system. She approaches Jagdish “Jolly” Tyagi (Arshad Warsi), the small-time lawyer we last saw in the first film. At first, he turns her away, citing costs. But guilt, empathy, and perhaps the faint memory of his own struggles force him to relent.

Enter the second Jolly—Jagdishwar “Jolly” Mishra (Akshay Kumar), whose more polished, slightly more idealistic persona clashes instantly with Tyagi’s scrappy cynicism. Their rivalry—at once comedic and biting—drives the film. The two Jollys end up facing off in court, not merely over the widow’s case but over their very philosophies of lawyering.

Presiding over this battle is Judge Sunder Lal Tripathi (Saurabh Shukla), who by now is the soul of the franchise. His courtroom becomes a theatre of absurdity, satire, and truth, where witty exchanges fly as fast as emotional truths land. Around them circle bureaucrats, land developers, and politicians—none painted as moustache-twirling villains, but all complicit in a system designed to exhaust the poor into silence.

The climax does not hand out a neatly ribboned victory. Instead, it delivers a verdict that forces both lawyers—and the audience—to reckon with the cost of justice: sometimes it arrives, but often too late to heal the wound.

—

Performances: The Human Pillars of the Courtroom

Akshay Kumar: Charm Meets Conscience

Kumar reprises his Jolly with both gravitas and mischief. He excels in the lighter stretches—his comic timing remains sharp—but his finest moments are quieter ones, particularly when Mishra confronts the despair underpinning the widow’s fight. He resists overplaying, allowing restraint to speak louder than theatrics.

Arshad Warsi: The Reluctant Hero Returns

For long-time fans, Warsi’s return is a gift. His Tyagi is older, wearier, perhaps more cynical than before. His humour remains effortless, but it’s his portrayal of a man torn between self-interest and conscience that leaves a mark. Warsi gives us the underdog again, reminding us why audiences rooted for him in the first place.

Saurabh Shukla: A Judge Beyond the Bench

If there is a crown jewel in this trilogy, it is Saurabh Shukla’s Judge Tripathi. His presence lifts every frame, oscillating between satire, warmth, and sudden bursts of moral clarity. He mocks lawyers, reprimands bureaucrats, and occasionally delivers lines that feel less like dialogue and more like universal truths. He is both comic relief and conscience keeper—a rare balancing act that only Shukla could achieve.

Seema Biswas: Pain Embodied

As Janki, Biswas is devastating. She doesn’t resort to high-pitched melodrama; her silences, her controlled grief, her dignity in despair, all make her the beating heart of the narrative. She reminds us that behind every legal battle is a life, already fractured before the gavel strikes.

Supporting Cast: Adding Layers

Huma Qureshi (as Mishra’s partner) and Amrita Rao (as Tyagi’s wife) inject warmth and occasional humour but remain underwritten, a recurring flaw of the franchise.

Gajraj Rao and Ram Kapoor lend weight to the depiction of systemic rot, never caricatured, but chilling in their casual exercise of power.

—

Direction and Writing: Subhash Kapoor’s Tightrope Walk

Kapoor faces the challenge of juggling three tones: comedy, social critique, and drama. His script leans on wit to sugar-coat bitter truths, a strategy that works more often than not. The first half leans playful, sometimes even routine, but the second half grows darker, more introspective, with flashes of brilliance in courtroom confrontations.

Kapoor’s writing respects audience intelligence. He doesn’t sermonise; instead, he lets absurdities expose themselves. When a bureaucrat stumbles over excuses or when the two Jollys twist the law to their convenience, the humour comes not from jokes but from truth disguised as farce.

Yet the ambition occasionally weighs the film down. A tighter edit could have pruned redundant sequences, particularly songs that interrupt rather than complement. At 157 minutes, the film is a tad indulgent.

—

Cinematography, Editing, and Music

Rangarajan Ramabadran’s cinematography distinguishes sharply between landscapes: the dusty despair of Bikaner, the suffocating corridors of Delhi courts, and the sterile wealth of urban boardrooms. Each frame underscores the social chasm the film critiques.

The editing occasionally falters, particularly in the transition between rural tragedy and courtroom banter. Yet in the climactic exchanges, the cuts are taut, lending urgency to verbal duels.

The music—serviceable but forgettable—remains the weakest element. A couple of inserted tracks feel commercially mandated rather than organically born of the narrative. Background scoring, however, complements the tonal shifts adequately.

—

The Courtroom as Satire and Mirror

The courtroom sequences are the franchise’s soul, and here they are more ambitious than ever. Unlike previous instalments, the antagonism is less about a single villain and more about the system itself—a hydra-headed beast of corruption, indifference, and bureaucracy.

Humour is weaponised not to trivialise suffering but to highlight absurdities. When Judge Tripathi cracks a line about how land ownership disputes outnumber all other cases, the audience laughs—but uneasily, knowing it is not far from truth.

In many ways, the courtroom becomes a miniature India—where the poor plead, the powerful stall, and the judge tries desperately to balance scales that are already tilted.

—

Comparisons: From Jolly LLB to Jolly LLB 3

The Original (2013): A scrappy underdog tale, raw and biting, anchored by Warsi and Shukla.

The Sequel (2017): Glossier, with Akshay Kumar lending star power, broadening the franchise but risking over-polish.

The Third (2025): A fusion of both worlds—returning Warsi for authenticity, retaining Kumar for reach, and giving Shukla the throne he has quietly occupied all along.

If the first was freshness and the second was expansion, the third is consolidation, though at times it feels burdened by the weight of trying to be everything at once.

—

Audience Impact and Cultural Resonance

Farmer suicides, land disputes, and systemic bias are not novel themes in Indian cinema. Yet, few mainstream films address them with both humour and empathy. Jolly LLB 3 achieves resonance because it speaks a language audiences recognise: satire laced with truth.

The laughter in the cinema hall is never careless—it is uneasy, often followed by silence. By the end, when the widow receives justice on paper but not in life, audiences are left confronting the uncomfortable reality: the law may deliver verdicts, but justice remains elusive.

—

Strengths

Stellar performances, particularly Saurabh Shukla and Seema Biswas.

Chemistry between Kumar and Warsi, blending humour with ideological clash.

Sharp dialogues that balance satire and sincerity.

A socially resonant theme handled with dignity.

Weaknesses

Overlong runtime; some scenes drag unnecessarily.

Songs feel shoehorned in.

Female characters underwritten, despite strong performers.

Occasional tonal unevenness between comedy and tragedy.

—

Verdict: The Judge Still Rules

Jolly LLB 3 is not flawless, but it doesn’t need to be. What it offers is something rarer in commercial Hindi cinema: entertainment with conscience. It is a film that makes you laugh, yes, but also one that unsettles, reminding you that behind every case number lies a broken family, a grieving widow, a silent village.

It may not outshine the freshness of the first or the star-driven slickness of the second, but as a trilogy closer, it stands tall. Ultimately, it is Saurabh Shukla’s Judge Tripathi who emerges as the true hero of the series—a character who embodies law’s absurdity and its hope in equal measure.

Critics’ Rating: ⭐⭐⭐⭐ (4/5)

Box Office Rating: ⭐⭐⭐ (3/5)

Final Word: A must-watch for fans of courtroom dramas, satire lovers, and anyone who believes cinema should provoke thought as much as laughter.