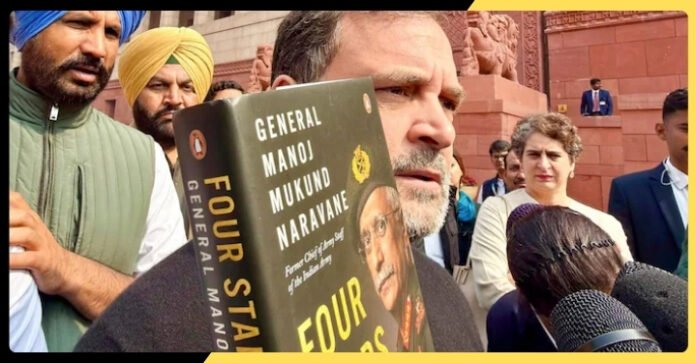

When reports first surfaced about a forthcoming book by former Indian Army Chief General Manoj Mukund Naravane, they appeared routine—almost dull in their normalcy. A senior military leader, recently retired, reflecting on decades of service. Publishing insiders spoke of a manuscript. Journalists said they had seen excerpts. Conversations hinted at anecdotes from the tense years along India’s borders. Then came the denial. The publisher, when contacted, said the book did not exist. No contract. No manuscript. No plans. And just like that, a routine announcement turned into one of the strangest publishing mysteries in recent memory.

The contradiction is stark. Multiple journalists insist they physically saw the manuscript or were briefed on its contents. Some claim to have read select passages. Others describe detailed chapter outlines that went well beyond rumor or speculation. Yet the publisher’s categorical denial has thrown those accounts into doubt. If the book doesn’t exist, what exactly did these journalists see? And why would a publisher distance itself so firmly from a project that seemed, until recently, very real?

General Naravane himself has offered little clarification, neither confirming nor fully denying the reports. His silence has only fueled speculation. For a figure known for measured public communication and institutional discipline, the ambiguity feels deliberate—or at least carefully managed. Observers note that this is not how false rumors usually die. Typically, an author or publisher issues a straightforward clarification. Instead, the mystery has thickened.

One possible explanation is timing. Books by former service chiefs often tread sensitive ground, especially when they involve recent operations, diplomatic tensions, or internal decision-making. Even when manuscripts are written with caution, last-minute concerns—legal, political, or strategic—can derail publication plans. A manuscript can exist without being officially acknowledged, particularly if negotiations collapse or approvals are withdrawn.

Another theory points to the fragmented nature of modern publishing. Early drafts may circulate among editors, agents, or collaborators before a formal contract is finalized. Journalists may have seen what they believed was a near-finished book, while the publisher later decided to walk away, allowing them to claim—technically—that the book “does not exist.” In such cases, existence becomes a matter of definition rather than fact.

Yet this explanation does not fully satisfy critics. The confidence with which early reports were made suggests more than a loose draft or exploratory proposal. Sources describe polished prose, structured chapters, and thematic coherence. Some even claim the book addressed leadership challenges during periods of heightened military tension, offering insights that would inevitably attract public and political attention.

That attention may be precisely the problem. In recent years, military memoirs worldwide have faced heightened scrutiny. Governments are increasingly wary of narratives that could complicate diplomatic relationships or reveal internal disagreements. In India, where civil-military balance and national security discourse remain highly sensitive, the stakes are particularly high. A book that was acceptable at one moment may become problematic at another.

There is also the possibility of deliberate misdirection. By allowing the book’s existence to be simultaneously affirmed and denied, all parties buy time. Public curiosity rises, but no definitive position is taken. If the book eventually appears, the mystery will have served as inadvertent publicity. If it never does, the confusion provides cover, allowing stakeholders to quietly move on without admitting a reversal.

For now, the “vanishing manuscript” remains suspended between reality and denial. The journalists who say they saw it stand by their accounts. The publisher stands by its refusal. And General Naravane, the man at the center of it all, has yet to offer the clarity that only he can provide.